For beauty, health, and protective reasons, Amazigh (Berber) women tattooed their faces, feet, arms, and other body parts. The historic tradition is quickly fading, nevertheless, as a result of how cultural dynamics and traditions change over time, as a result of globalization, and due to the impact of Islam on society.

Today’s tattooed Amazigh women were raised in a culture that valued and celebrated tattoos as an essential part of who they were. Over the course of their lives, the ladies saw an unanticipated shift in North Africa, when their tattoos, which had formerly made them desirable, became a source of shame.

Tattooing is a long-standing custom that is still present in many cultures today. The practice of tattooing has been continuously practiced by the Amazigh people in North Africa from pre-Islamic times.

Traditional Culture of tattoos in Amazigh women: Origins and Signs

Also Read: Facts about the Zulu People: Language, Religion and Culture

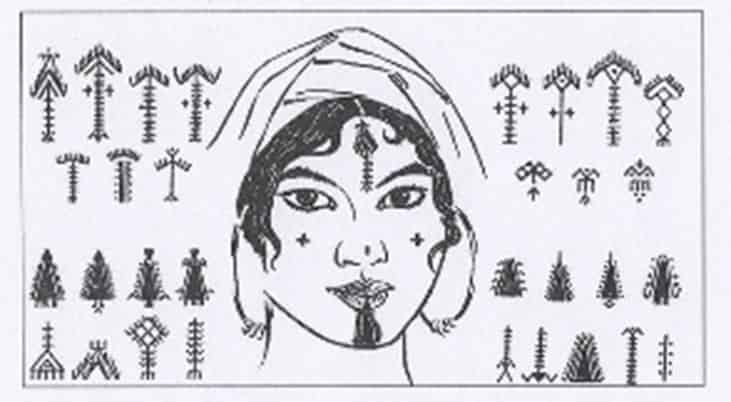

In the past, tattoos helped the nomadic Amazigh tribes identify members of various groups. The tattoos’ symbols, which were deeply ingrained in each group’s history and mission, acted as a unifying factor. Beyond aesthetic purposes, tattoos served as a means of transmitting family ties, telling tribal tales, and binding women to their territory. This practice is currently quickly dying out. The last generation to have participated in the practice are the elderly tattooed Amazigh women of today.

Origins of Amazigh tattoos

Tattooing is one of the oldest rites of Berber and Amazigh culture. It has its origins in the Pharaonic-Nubian period. Egyptian mummies dating from the eleventh dynasty (2500 years before our era) have indeed been discovered near Thebes and thus revealed tattoos on the torso, legs, and arms. Representing aligned dots or parallel lines, they suggest diverse and mystical interpretations. The majority of mummies whose gender has been identified are female.

The female Amazigh tattoo is linked to a set of ancestral rites. It symbolizes a social status, expresses a feeling, or is still used as an adornment, and suggesting a certain eroticism. In its function of resilience, it helps to overcome bereavement. The woman who has just lost her husband, brings the deceased's beard back to life on her face, as a token of her fidelity and warding off potential suitors. It could also ward off bad luck, and be a sign of the materialization of suffering.

The drawings are generally transmitted from generation to generation, reproduced by expert women, during their passages in the Chaouia villages along the way between Sahara, Hauts-Plateaux, and the mountains. In the oasis of the South, it seems that the women tattooed each other, as a family.

The practice of this art is seen little by little as socially devalued, from the seventies of the last century, undoubtedly following a more assertive anchoring of society in the practice of a more rigorous Islam. Indeed, Muslim thinkers, theologians, and jurists consider tattooing to be contrary to the Koran.

Women faithful to the ancestral tradition thought, according to popular belief, that they could escape the punishment of having their skin tattooed by covering the designs with henna. The practice of henna tattooing has gradually replaced permanent tattooing in parts of North Africa.

Tattoos signs of Amazigh women

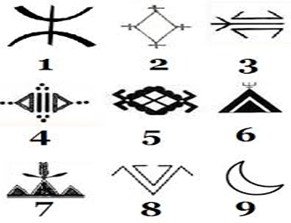

The "+" sign frequently appears on the cheek, or under the eye, and is called a "bird". It more specifically represents the imprint of a bird's paw, like the hawk, in Tamazight "igder". It is perceived as a sign of power and authority, hence a feeling of protection for the wearer. The person feels in fact sheltered from arbitrary domination.

"Cross" with equal branches

Being able to be interpreted as an unconscious reminiscence of the "Christian past of Barbary". but, the cross reveals very different interpretations. It is first of all a basic element in the fields of decoration such as stelae, weaving, pottery, or even painting. The crossing of the vertical line with the horizontal line at an equal distance is a symbol that has been universally used for millennia and already in the Stone Age.

Among the Gauls, this kind of cross appeared regularly on handicrafts, jewelry and coins. In Central America, this cross refers to the 4 winds, the source of rain. Finally, the Cross ultimately presents a meaning of perfection and balance, combined with a sense of fairness and equality.

Different representations of the sign of Tanit

Tanit is a goddess responsible for looking after fertility, births and growth. It protects life. She is the tutelary goddess of Sarepta (Phoenicia). She was the consort of the god Baal Hammon. We find this sign on Carthaginian stelae or mosaics and ceramics.

Tanit's sign is an anthropomorphic symbol. It symbolizes the connection of the terrestrial world with the celestial world.

This sign is also found in the pharaonic tradition. Some see in the cross of Agades, the tuareg symbol of Niger, the preservation of the sign of Tanit.

The Moon

The moon is credited with magical powers that women know how to capture according to certain Berber traditions, the sign of the moon tattooed near the eye would have to do with this interpretation.

In the Tamazight language, the month and the moon are the same word, aggur. With the star in its center, it would evoke paradise. The presence of these symbols in tattoos obviously has no connection with other religious or national uses and their current meanings.

Berber Woman Palm Tattoo

The palm has for some women the (unspoken) status of mother goddess, source of wealth and protective figure like the protective shadow of the palm tree. She is a symbol of life, as well as the spring or the water, which could explain these ornate representations.

In the tradition of ancient Egypt, we find the reference to the palm as a symbol of fertility. Indeed, the palm lives a long time and bears fruit until death.

Partridge's Eye

In the shape of a diamond, it represents the bird itself, a symbol of beauty, agility, cunning, or rather wisdom, qualities that would give them a certain freedom. The partridge is reputed to be difficult to tame. Thus, to represent this sign on oneself is to attract what it symbolizes.

Conclusion

The culture of tattooing has ceased to continue in most of Tamazgha. The disappearance of the tradition is not only linked to the occupation and the role of Islam, but also to the urbanization and modernization of Amazigh societies. Traditional tattoos, such as those of Amazigh women are now seen as unsuitable and non-modern.

In urban and rural regions the tattooing tradition rarely continues. There are no longer young women getting tattoos in most areas, but many of the women in the older generation still have tattoos on their faces, hands, and feet.

Husbands and families who encouraged or forced women to get tattoos at a young age now suggest they get their tattoos removed or covered. Tattoo symbols which were passed down between generations will not continue past their skin.

The tradition of tattooing connects the Amazigh people to any communities of indigenous people worldwide who use tattooing as a form of expression, healing, and protection. Around the world, the traditions of indigenous groups face the growing threat of globalization and modernization, which has in turn led to the disappearance of many indigenous tribes and practices.

It is up to the Amazigh people to decide what will be lost with the end of a centuries-old tradition. How will Amazigh's preserve the photographs, symbols, purposes, and stories of the tattooed Amazigh women for the future How they will protect the ancient traditions that remain

Bibliography

- Aguilar, A. Tattoos as worldviews A journey into tattoo communications using standpoint theory. Conference Papers, National Communication Association, 2001

- Ahmed, L. Women and gender in Islam. New Haven, Yale College, 1992

- Atkinson, M . Tattooed The sociogenesis of a body art, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2003

- Bauman, K. Tattoo stories Bodies revealing life, Conference Papers National Communication Association, 2008

- Becker, C. Amazigh arts in Morocco Women shaping Berber identity. Austin, University of Texas Press, Texas, 2006

- Bernasek, L. Artistry of the everyday beauty and craftsmanship in Berber art, MA Peabody Museum Press, Harvard College, 2008

- Courtney-Clarke, M. Imazighen, the vanishing traditions of Berber women, Clarkson Potter Publishers, New York, 1996

- Diaconoff, S. Myth of the silent woman Moroccan women writers, University of Toronto Press, 2009

- Eickleman, D. Moroccan Islam Tradition and society in a pilgramage center, University of Texas Press, Print, 1976

- Fischer, A and Kohl, I.Tuareg society within a globalized world Saharan life in transition, I.B. Tauri, London and New York, 2010

- Gellner, E & Micaud, C. (1973). Arabs and Berbers from tribe to nation in North Africa, D. C. Heath and Company, London and Ghabra, H. S, 2018

- Gröning, K. Decorated skin a world survey of body art, Thames & Hudson, London, 1997

- Ilahiane, H. Historical dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Scarecrow Press, 2017

- Krutak, L. (2010). Tattooing in North Africa, the Middle East and Balkans, Retrieved April 04, 2019

- Laroui, A. The history of the Maghreb, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1977

- Mifflin, M. Bodies of subversion a secret history of women and tattoo, PowerHouse books, Brooklyn, New York, 2013

- Pitts, V. In the flesh The cultural politics of body modification, New York Palgrave. Pritchard, 2003